The spirally wound cylindrical cell is particularly convenient to manufacture. Why then are these cells typically small? To answer this question, heat removal must be considered. A number of simplifying assumptions will be made, but the basic physics will provide clear guidance for the engineer. As was discussed in the previous chapter, during operation heat is generated in the cell. Here we will assume a resistive cell with a uniform rate of heat generation, ![]() (see Illustration 7.5). To solve for the temperature in the battery, we start with a differential energy balance:

(see Illustration 7.5). To solve for the temperature in the battery, we start with a differential energy balance:

(8.26)![]()

This equation is applied to a cylindrical battery. keff is an effective thermal conductivity in the radial direction. There are no variations in the theta direction and we assume that the cell is long in the z-direction so that the problem becomes one dimensional, and in cylindrical coordinates,

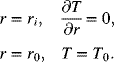

For the spirally wound cell, a sheet of current collectors, electrodes, and separators are wound around a shaft of radius ri, and the final radius of the winding is r0 (Figure 8.9b). Two boundary conditions are needed for Equation 8.27. We assume that no heat is conducted to the shaft and that the temperature is specified at r0:

Equation 8.27 is separable and upon integration, the solution is

Figure 8.13 shows the variation in temperature with radial position. As seen in Illustration 7.5, the rate of heat generation is proportional to the current, and therefore proportional to the C-rate.

Next, we consider what happens when more windings are added to the cell. The capacity of the cell is directly proportional to the length, L, of the winding around the shaft. The diameter or radius of the winding can be determined from basic geometric considerations:

δ is the thickness of the sheet that is being wound.

The results are shown in Figure 8.13. As the capacity of the cell is increased (by adding windings), the temperature near the center, ri, increases. This relationship is shown in Figure 8.14. The combination of increased capacity and higher rates is limited by the maximum allowable temperature of the cell. Even though it is efficient to manufacture larger cells by winding more material, heat removal constrains this approach to adding capacity. This illustration also assumed that the temperature on the outside of the cell is fixed. A more realistic boundary condition would relate the rate of heat removal by conduction to the heat removal rate from the surface by convection. This refinement would result in even higher temperatures inside the battery.

Storing large amounts of energy has inherent safety concerns. Although the challenge is best known with lithium-ion cells, many different types of cells can undergo thermal runaway. As illustrated previously, the operating temperature of a cell is determined by the heat generation inside the cell and the heat removal from the cell. This analysis assumed that the rate of heat generation was equal to the rate of heat removal; that is, a kind of steady state. As the rate of heat generation increases, the cell temperature rises until the rate of heat removal balances the rate of generation. Thermal runaway, in contrast, refers to a transient condition where the internal cell temperature rises uncontrollably. For aqueous batteries, thermal runaway is usually associated with a constant voltage or float charge. At constant voltage, the current decreases during the taper charge. If the temperature were to rise in one area, the resistance of the cell decreases (lower ohmic and activation overpotentials) and thus the local current density increases. There is, however, negative feedback in this system. As more charge is passed, the local equilibrium potential increases; and therefore, the overpotential decreases, causing the current density to go lower. What happens, during float charge or when most of the current is going into gas evolution? The current flowing does not change the local SOC of the electrode, and therefore the negative feedback is removed. Now more current results in more heat generation and a temperature rise. Higher temperature lowers the polarization, leading to more current and more heat generation. If not controlled, thermal runaway can occur.

8.10 Mechanical Considerations

Mechanical effects are important in battery design and operation, and are often underappreciated. They impact battery performance and longevity at a range of length scales from the stress that develops in submicrometer-sized particles of an active material to the macroscale structural requirements of a large battery pack such as the 2-ton battery pack used in a submarine. Frequently, the effects are specific to a particular chemistry and cell design. A few of these effects will be mentioned in this brief introduction, but the analysis is by no means complete or in-depth.

First, we consider variations in the volume of a cell. Volume changes can result from reactants and products with different densities. For instance, it is common for the negative electrode of a lithium-ion cell to experience a volume change of about 10% with lithium intercalation. At the same time, the positive electrode may change only 2% or less. Thus, there is a net change in the volume of a lithium-ion cell with state-of-charge. Volume changes in battery cells also occur as components expand and contract with changes in temperature. Internal stresses can be caused by thermal expansion as a result of different volume changes for the different materials that make up the cell. Whether caused by the reaction or by temperature, allowance for volume change is an important part of battery design.

Second, it is necessary for cell design to provide mechanical stability. Generally, we cannot let the cells be completely unrestrained (to account for volume changes, for instance). Cells in mobile applications are also subject to vibration and shock. Again, the specific needs vary significantly with the chemistry of the cell and with the particular application. For example, a small amount of compression is desired in order to prevent delamination (connected to volume change) in cells where the electrodes are coated onto a current collector. What if the compression is too high? Excessive compression can lead to creep of the polymer separator, causing a reduction in its porosity and resulting in increased resistance or increased mass-transfer overpotentials. This possibility is explored further in Illustration 8.4. Other cells will have different needs. Our purpose in this short section was to briefly introduce you to the mechanical issues that are an essential aspect of cell design and operation.

ILLUSTRATION 8.4

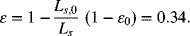

In this illustration we consider the impact of compression on the separator of a lithium-ion cell. The strain for two electrodes of a cell sandwich is given by

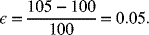

where ![]() is the thickness in the assembled state (fully discharged). The maximum thickness occurs when the electrode is fully charged, which for the lithium-ion cell under consideration is 105 μm. If the assembled thickness of the electrodes is 100 μm, the strain is calculated as

is the thickness in the assembled state (fully discharged). The maximum thickness occurs when the electrode is fully charged, which for the lithium-ion cell under consideration is 105 μm. If the assembled thickness of the electrodes is 100 μm, the strain is calculated as

The cell sandwich consists of a Cu current collector, the negative electrode, a polymer separator, the positive electrode, and an Al current collector. The elastic moduli of the other components are at least an order of magnitude higher than that of the separator (effective modulus for solvent-soaked porous separator). Therefore, the separator will be the first component of the cell to undergo plastic deformation. If the separator has a porosity of 0.45, and a stress-free thickness of 30 μm, what is the final thickness and porosity of the separator, as well as the stress?

SOLUTION:

Assuming a negligible modulus for the separator, its thickness would be reduced by 5 μm to 30 − 5 = 25 μm. The volume of polymer is unchanged, so that the new void volume (porosity) is given by

Under these assumptions, there would be no stress in the assembly.

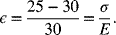

Let’s check to see if the assumption of plastic deformation is reasonable. The strain experienced by the polymer is

Using an effective modulus, E, of 1 GPa, the stress is 170 MPa, which is well above the yield stress of 20 MPa. This would result in plastic deformation of the separator.

Closure

In this chapter, the process of selection and design of batteries was introduced. The key factors are discharge time, energy, and voltage. The discharge time profoundly influences the electrode and cell design. The energy, or capacity, determines the size of the battery. The desired voltage is achieved by connecting multiple cells together in a string. Capacity is changed by adding more active material, and several means of accomplishing this addition were considered, particularly with regard to rate capability. Proper monitoring and control of the current to the individual cells in the battery is critical during operation, but particularly during charging. Finally, the importance of thermal and mechanical aspects of battery design was introduced.

Further Reading

- Crompton., T.P.J. (2000) Battery Reference Book, Reed Educational and Professional Publishing Ltd.

- Keihne, H.A. ed., (2003) Battery Technology Handbook, CRC Press.

- Reddy, T. and Linden, D. (2010) Linden’s Handbook of Batteries, McGraw Hill.

Problems

8.1. You are asked to configure a battery with the following requirements: 1512 W·h, 200–400 VDC, and a discharge time of 3 hours. A lithium-ion battery is available with the following specifications at a rate of C/3: nominal voltage of 3.5 V and is manufactured in two sizes: 3.3 and 4.5 A·h. The cutoff potential of the cells is 2.75 V, and the maximum charging potential is 4.1 V. What configuration would you recommend?

8.2. For the same battery specified in Problem 8.1, what would be the ideal capacity in A·h of the individual cells to achieve as close as possible to 300 VDC for the nominal voltage of the battery? Compare this answer to the configuration found in Problem 8.11. Which would be preferred and why?

8.3. Derive Equation 8.23 for the maximum power for an ohmically limited cell. What is the expression for maximum power if there is a cutoff potential greater than one half of the open-circuit potential?

8.4. You have a battery with a configuration of 50S-3P. The specifications for individual cells are open-circuit potential 3.1 V, an internal resistance of 2 mΩ, and a capacity at 1C of 7 A·h. Assuming the cells are ohmically limited, what is the maximum power that can be achieved? If individual cells have a cutoff voltage of 2.75 V, what is the maximum power? What must the value of the external resistance be to ensure that less than 5% of the available power is lost because of the connections?

8.5. The Tesla Model S electric car uses 6831 cells for the battery. The cells are the so-called 18650 (cylindrical, 18 × 65 mm) lithium-ion cells, each with a capacity of 3.1 A·h and a nominal voltage of 3.6 V. What is the capacity in kW·h for the battery? How might you configure these cells to make a pack? Discuss the challenges with packaging the large number of cylindrical cells. A battery voltage of 300–400 V is generally desired.

8.6. The nominal design of a 20 A·h cell is shown below. The tabs for current collection are on the same side and the dimensions of the cell ![]() are 140 × 100 × 15 mm3. Alternative designs are being considered.

are 140 × 100 × 15 mm3. Alternative designs are being considered.

| Option | Capacity [A·h] | L [mm] | W [mm] | Tabs |

| Nominal | 20 | 140 | 100 | Narrow, same side |

| 1 | 6.67 | 140 | 100 | Narrow, same side |

| 2 | 20 | 200 | 140 | Narrow, same side |

| 3 | 20 | 250 | 120 | Opposite sides, wide |

- Assuming that the electrodes and current collectors are unchanged and that the thickness of the current collector is small relative to the cell thickness, what are the cell thicknesses of the alternate designs?

- Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of these alternatives. For option 1, three cells are required to keep the capacity the same. Consider the following in your answer:

- heat removal

- uniformity of current density across the planform

- rate capability, resistance of current collectors and tabs

8.7. L is the characteristic dimension of the electrode, δ is the thickness of the current collector, and σ is its electrical conductivity. The width of the electrode, perpendicular to the section illustrated below, can also be assumed to have a length equal to L so that the area of the electrode exposed to the electrolyte is L2. Show that if the current density over the electrode is constant (iy), the resistance to current flow in the current collector is ![]() . This “average” resistance is defined as the total current that enters the current collector divided by the voltage drop across the current collector. Assume that electrical connection to the current collector is made at x = L, and treat current flow in the current collector as one-dimensional. Under these conditions,

. This “average” resistance is defined as the total current that enters the current collector divided by the voltage drop across the current collector. Assume that electrical connection to the current collector is made at x = L, and treat current flow in the current collector as one-dimensional. Under these conditions, ![]() . How should δ be scaled if it is desired to keep the resistance ratio of the current collector and electrochemical resistance constant? In other words, how should the thickness of the current collector be changed in order to maintain a constant resistance ratio if the size of the electrode, L, were increased or decreased?

. How should δ be scaled if it is desired to keep the resistance ratio of the current collector and electrochemical resistance constant? In other words, how should the thickness of the current collector be changed in order to maintain a constant resistance ratio if the size of the electrode, L, were increased or decreased?

8.8. For current collectors in lithium-ion cells, copper foil is used for the negative electrode and aluminum foil for the positive. Often the aluminum foil is about 1.5 times as thick as the copper. Why is this done?

8.9. Problems 7.3 and 7.4 examined the LiI battery that is used for implantable pacemakers. There is also a desire to have a defibrillator capability, where a short high pulse of power is occasionally required. Recall that the separator is formed in place from the overall reaction. Assume that all of the resistance is in the separator. At 37 °C, the LiI electrolyte has an ionic conductivity of 4 × 10−5 S·m−1. The open-circuit potential of the LiI cell is 2.8 V. What is the maximum thickness of LiI allowed so that the power requirements for the defibrillator (3 W) can be met? LiI has a density of 3494 kg·m−3. The cell area is 13 cm2. Is it feasible to redesign this LiI cell to include the defibrillator feature and still meet the energy and life requirements? Explain why or why not.

8.10. Using data from Figure 8.12, determine charging and discharging resistance of the cell. The answer should be in Ω·m2. Compare these values with the ohmic resistance of the same cell. Discuss why the values are different.

8.11. For a 125 A·h lead–acid cell, after a discharge from 100 to 20% SOC, 119 A·h was required to restore the cell to a full state-of-charge. Calculate the charge coefficient. How might this charge coefficient change with the rate of discharge? Temperature?

8.12. During charging of a lithium-ion battery, lithium ions are transported to the negative electrode, where they are reduced and then intercalate into the graphite active material. One limitation on the rate of charging is the concentration of lithium at the interface. If the rate is too high, then lithium metal can plate, which is a dangerous situation. This level of lithium is sometimes referred to as the saturation level.

- Qualitatively sketch the concentration profile of lithium in the electrolyte and in the graphite. How do these profiles change with the rate of charging?

- Discuss differences that correspond to the following charging protocols: (1) constant current density of 20 A·m−2 until the saturation level of lithium is reached, and (2) repeated pulses of charging at 25 A·m−2 for 3 seconds followed by a lower rate of 5 A·m−2 for 1 second.

8.13. Lithium-ion batteries have self-discharge rates of 1–2% per month. If two adjacent cells in a long string connected in series have rates of self-discharge of 1 and 2% per month, respectively, and the battery is fully charged each month, how long before the SOCs of these two cells vary by 5%? The rate of self-discharge, however, can be as high as 5% in the first 24 hours. If the initial rates of self-discharge for the two cells are 3 and 5%, respectively, how does the answer change? What role would the battery management system play in this scenario?

8.14. A cylindrical cell is fabricated by winding the electrodes around a shaft with a diameter of 2 mm. The length of the winding is 1.8 m and its thickness is 0.5 mm. If the rate of heat generation is 50 kW·m−3 and the effective conductivity in the radial direction is 0.15 W·m−1·K−1, what is the maximum temperature of the cell at steady state?

8.15. Rather than specifying the temperature at the outside of the cell as was done in Section 8.9, in practice heat is removed by forced convection. What is the appropriate boundary condition? Use h for a heat-transfer coefficient and T∞ for the temperature of the fluid. Solve the differential equation to come up with an equation equivalent to (8.28). In general, would liquid or air cooling be more effective? Why?

8.16. The analysis in Section 8.9 is for a cylindrical cell. Develop a similar analysis for a prismatic cell. Assume that all the heat is removed from the top and bottom of the cell (i.e., assume there is no heat loss from the sides). Furthermore, heat is removed from the bottom of the cell using convection through a cold plate (hc, Tc) and from the top to ambient, also by convection (ha, Ta).

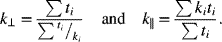

8.17. Electrodes for lithium-ion cells are made by coating active material onto both sides of metal foils. The coated electrodes are then wound with a polymer separator or stacked to form a cell sandwich. Given the dimensions and physical properties in the following table, calculate the effective conductivity in the in-plane (||) and through-plane (![]() ) directions for a prismatic cell sandwich. What are the implications for the design of a cell and heat removal? Use the following formulas:

) directions for a prismatic cell sandwich. What are the implications for the design of a cell and heat removal? Use the following formulas:

| Component | Thickness, ti [μm] | Conductivity, ki [W·m−1·K−1] |

| Al current collector | 45 | 238 |

| Positive electrode material | 66 | 1.5 |

| Cu current collector | 32 | 398 |

| Negative electrode material | 96 | 1.0 |

| Separator | 50 | 0.33 |

8.18. Negative feedback was mentioned in Section 8.9 as an important feature in preventing thermal runaway of cells. For the following instances, explain the role of feedback in either reducing or exacerbating temperature variations.

- Because of ohmic resistance of the current collectors, the current density over the electrode is not uniform. The current density is higher near the tabs.

- During normal discharge of a single cell, heat removal is not uniform and a local temperature rise occurs at one spot in the planform of a cell.

- For valve-regulated lead–acid battery thermal runaway is a possibility during float charge at a fixed voltage. In these cells, rather than being vented, oxygen generated at the positive electrode is directed to the negative electrode where it reacts exothermically. Up to 90% of the current during float charge goes to this oxygen recombination.

8.19. Consumers desire to charge their electric vehicles as quickly as a conventional car can be refueled. If time for refueling with gasoline is about 2 minutes, at what C-rate would the battery need to be recharged in the same period? For a 50 kWh battery, what power corresponds to this rate? Frequently, researchers report extremely high rates of charge and discharge for tiny experimental cells, typically with very thin electrodes. What challenges exist in translating these results to a full-sized electrical vehicle battery?

8.20. A coin cell is prepared by sealing layers of material in a can. A spring washer is included to apply a controlled force on the assembly. Using the data for the layers below, if the final thickness of the sandwich is 2.4 mm, what is the normal stress? The spring has an initial thickness of 2 mm and a spring constant of 120 kN·m−1. The diameter of the layers is 1.4 mm.

| Cell component | Initial thickness [mm] | Elastic modulus [GPa] |

| Anode spacer | 0.50 | 210 |

| Anode | 0.070 | 15 |

| Separator | 0.025 | 1 |

| Cathode | 0.070 | 70 |

| Cathode spacer | 0.50 | 210 |

Leave a Reply