As we consider the energy storage requirements for the start–stop hybrid, it is important to know the power required as a function of time. The intended driving schedule and many of the specifics for the vehicle are not needed for design of the energy storage system for this type of hybrid, since the RESS does not provide power to move the vehicle. The needed power and energy requirements can be approximated from a simple cycle with just three features that are repeated: engine off, engine restart, and recharge. The three states are shown in Figure 12.9, where positive values represent energy being supplied by the energy storage device and negative values correspond to recharge. We see that, in addition to relatively long periods (on the order of a minute) of charging and discharging, a high pulse of power is needed for restarting the engine. Sizing an energy storage device for the power and energy needs dictated by the cycle shown in Figure 12.9 is straightforward as shown in Illustration 12.3.

Here we contemplate two options for energy storage: electrochemical double-layer capacitors (EDLC) and batteries. Each must meet both the energy and power needs of the cycle. Although the fundamentals of these devices have been covered in earlier chapters, we introduce a couple of additional considerations. For batteries, we include cycle life and capacity turnover (Section 12.3). Examining the energy required to complete a typical cycle as shown in Figure 12.9, we observe that the capacity of the battery needed is quite small. A typical starting–lighting–ignition (SLI) battery (Chapter 8) for a conventional vehicle has a rated capacity on the order of 60 A·h. Why is the capacity so much larger than that required to start the vehicle? Part of the answer has to do with providing the requisite power, but low-temperature performance and the useable life of the battery are also important.

By contrast, EDLC performance degrades only minimally over tens of thousands of cycles; therefore, cycle life is generally much less of an issue. We learned in Chapter 11 that the energy stored in a capacitor is ½ CV2, although the amount of useable energy in an EDLC is less as will be discussed shortly. Similar to the way that the SOC window for a battery limits its useable energy, there are real-world limits for the EDLC. The SOC window is limited for a battery to preserve its life—the reasons for limiting the EDLCs are different. The maximum voltage is limited by physical constraints—for example, the stability limit of the electrolyte. Also, the voltage of the capacitor is directly proportional to its charge. Thus, the output voltage decreases linearly from a maximum to zero during constant-current discharge (Figure 11.9 compares the voltage of a battery and EDLC during discharge), and power electronics are needed to maintain a constant output potential. As a practical design matter, the output voltage may only be allowed to decrease to half of the maximum potential (Vmax). Since the amount of stored energy is proportional to the voltage squared, one-fourth of the energy stored in the capacitor cannot be used if the voltage is limited in this fashion, as illustrated in Figure 12.10. The usable energy is therefore equal to three-fourths of the maximum energy when the minimum voltage is equal to Vmax/2.

When regenerative braking is used, it is desirable to keep some capacity available at all times to allow energy recovery. Thus, the charge may be stopped before the maximum voltage, Vmax, of the EDLC is reached. The difference between the nominal voltage and maximum voltage (refer back to Figure 12.5) will determine the amount of energy that may be unused on the high end.

On the other hand, compared to a typical secondary battery, EDLCs self-discharge much more quickly. Thus, the EDLC must be made larger to make up for the self-discharge, or combined with a battery to form a hybrid RESS.

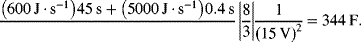

ILLUSTRATION 12.3

Size a RESS for a start–stop hybrid using the profile shown in the table. Assume 12,500 stops per year and a 5-year life. Consider both a lead–acid battery and an electrochemical double-layer capacitor. The battery has a capacity turnover of 800, a nominal voltage of 12 V, and a specific energy of 42 W·h·kg−1. EDLC modules (15 V, 230 F) are available with 3 mΩ resistance (ESR). Each module has a mass of 1.7 kg.

| Power [W] | Time [s] | |

| Engine off, Pacc | 600 | t1 = 45 |

| Restart, Ps | 5000 | t2 = 0.4 |

SOLUTION:

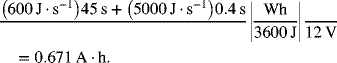

First, let’s size the lead–acid battery. Calculate the A·h associated with one cycle:

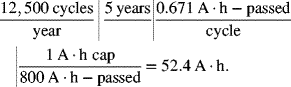

Now, calculate the charge capacity needed for the specified 5-year lifetime (see Equation 12.4).

The last term on the left-hand side of the equation follows directly from the definition of capacity turnover. The calculated capacity corresponds to ![]() .

.

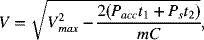

Next, we calculate the size of the EDLC. To do so, we assume that cycle life is not limiting. The EDLC is consequently sized to meet the energy and power needs of the cycle. Given the energy required per cycle and assuming 15 V for the capacitor (as specified above), Equation 12.5 provides the capacitance, which is a measure of size for the capacitor. Note that there is no need for additional capacity at the “top end” since the start–stop hybrid does not include regenerative braking. We have not included allowance for self-discharge in our design.

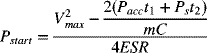

Given the above module size (230 F), a minimum of two modules connected in parallel are needed. The power that the capacitor can deliver must also be considered. The maximum power from a capacitor is given by (see Chapter 11)

For the start–stop hybrid, it is critical that we have sufficient power to start the engine after running the accessories during the time that the vehicle is stopped. Therefore, the potential, V, that is used in this equation is the voltage of the capacitor after 45 seconds of supplying accessory power. In addition, to ensure that the power is available throughout the start portion of the cycle, we include the energy consumed during engine start in our calculation of the voltage drop. Assuming that the capacitor starts with a voltage of 15 V = Vmax, the potential at the end of the start cycle, determined by calculating the voltage drop associated with the energy consumed, is

where m is the number of modules and C is the module capacitance. Therefore, the power available at the end of the start cycle is

For m = 2, there is about 8 kW of power still available. Thus, there is more than sufficient power to start the engine. We conclude that two modules are needed; the mass is 3.4 kg. Clearly, this mass is much lower than the battery mass estimated above. Remember, however, that capacitors do not hold a charge for long periods, and a battery would be needed to start the engine in the event that the capacitors had discharged due to lack of use of the vehicle.

Leave a Reply