We’ve seen that the cells are connected in series to achieve the desired voltage of the battery. The capacity is increased by adding cell strings in parallel. However, each cell requires its own casing, safety reliefs, terminals, and connections, to which we will collectively refer to as ancillary. Clearly, we would like to reduce the volume, mass, and complexity associated with these ancillaries. One way to accomplish this is to group cells into modules as was discussed briefly in the previous section. An alternative way is to reduce the number of cells by increasing the size of the individual cells. We will examine this alternative now.

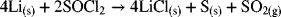

The reason for increasing cell size is to increase its capacity, recognizing that the capacity of a battery is a function of the amount of reactive material present. Consequently, we begin by developing a quantitative relationship between size (volume) and capacity. To do this, we use a primary lithium thionyl chloride battery as an example. The overall reaction for this battery is

Two of the reaction products are solids that deposit at the positive electrode; the other product is sulfur dioxide gas. Also, note that the ![]() electrolyte participates in the reaction. Therefore, the cell volume must include space for the gas that is formed, and should ideally account for the decrease in electrolyte volume as the reaction proceeds. For our purposes here, we adopt the battery construction shown in Figure 8.3. The negative electrode is a foil of lithium metal, and the positive electrode is porous carbon. The volume of the cell is the sum of the volume of individual components: negative electrode, positive electrode, separator, positive current collector, negative current collector, and the excess volume. The total cell volume is therefore

electrolyte participates in the reaction. Therefore, the cell volume must include space for the gas that is formed, and should ideally account for the decrease in electrolyte volume as the reaction proceeds. For our purposes here, we adopt the battery construction shown in Figure 8.3. The negative electrode is a foil of lithium metal, and the positive electrode is porous carbon. The volume of the cell is the sum of the volume of individual components: negative electrode, positive electrode, separator, positive current collector, negative current collector, and the excess volume. The total cell volume is therefore

For a given capacity Q [A·h], the negative electrode (lithium) volume is given by Faraday’s law

The quantity 3600 converts A·h to coulombs. fa is a design factor that is included because excess lithium is needed. Since current is also collected by the lithium foil, we don’t want to consume all of the lithium, even at full discharge.

The positive electrode is a porous carbon material. It must have an initial pore volume that is in excess of the volume of solid reaction products resulting from the discharge. The volume of solids produced is the sum of the sulfur and lithium chloride, and both are proportional to the capacity.

(8.10)![]()

ε is the initial void volume fraction of the positive electrode. fc is a second design factor that represents additional porous volume in the positive electrode. Similar to the excess lithium required, some pore volume must remain, even at full discharge. The next three volumes are, respectively, those associated with the separator, negative current collector, and positive current collector.

where ![]() represents thickness. Each of these volumes is proportional to the separator area, which wraps around both sides of the positive electrode for the design shown in Figure 8.3; therefore, the separator area is divided by two to get the area for the positive current collector. Volume is also needed to accommodate the gas that is formed. We won’t go into details for calculating the excess volume needed, but it stands to reason that it also should be proportional to the capacity, which we will express as

represents thickness. Each of these volumes is proportional to the separator area, which wraps around both sides of the positive electrode for the design shown in Figure 8.3; therefore, the separator area is divided by two to get the area for the positive current collector. Volume is also needed to accommodate the gas that is formed. We won’t go into details for calculating the excess volume needed, but it stands to reason that it also should be proportional to the capacity, which we will express as ![]() . Substituting this relationship and Equations 8.9, 8.11 and 8.12 into Equation 8.8 gives

. Substituting this relationship and Equations 8.9, 8.11 and 8.12 into Equation 8.8 gives

(8.13) Equation 8.13 provides the desired relationship between volume and capacity. It would seem that we can now easily determine the change in volume necessary to increase the capacity by a desired amount. However, this relationship does not tell the entire story. To explore the issue further, let’s imagine that we have an existing cell design with capacity Q0 and volume

Equation 8.13 provides the desired relationship between volume and capacity. It would seem that we can now easily determine the change in volume necessary to increase the capacity by a desired amount. However, this relationship does not tell the entire story. To explore the issue further, let’s imagine that we have an existing cell design with capacity Q0 and volume ![]() . We want to increase the capacity, but keep the discharge time unchanged. If the separator area is held constant, the nominal current density is directly proportional to the capacity; therefore, an increase in capacity by a factor of 2 would require that the current density be doubled. From Equation 8.13, the smallest increase in volume needed to double the capacity results from keeping the separator area, separator thickness, and the thickness of the current collectors constant. This is shown as Option 1 in Figure 8.4 where the separator area, As, is held constant and the thickness of each of the two electrodes is increased. The new volume can be calculated from Equation 8.13 and is shown as O1 in Figure 8.5. Unfortunately, if you followed this procedure in practice, you would likely be disappointed. Why? To answer this question, let’s examine what happens to the nominal current density as the cell size is changed.

. We want to increase the capacity, but keep the discharge time unchanged. If the separator area is held constant, the nominal current density is directly proportional to the capacity; therefore, an increase in capacity by a factor of 2 would require that the current density be doubled. From Equation 8.13, the smallest increase in volume needed to double the capacity results from keeping the separator area, separator thickness, and the thickness of the current collectors constant. This is shown as Option 1 in Figure 8.4 where the separator area, As, is held constant and the thickness of each of the two electrodes is increased. The new volume can be calculated from Equation 8.13 and is shown as O1 in Figure 8.5. Unfortunately, if you followed this procedure in practice, you would likely be disappointed. Why? To answer this question, let’s examine what happens to the nominal current density as the cell size is changed.

With the separator area held constant, for two times the capacity, the nominal current density is twice as large. This immediately leads to a couple of concerns. First, with a larger current density, the ohmic, activation, and concentration polarizations of the cell increase, resulting in a lower cell potential for a given current. At this higher current density, the cutoff voltage for the cell will be reached sooner, leading to a lower effective capacity. Second, as we saw in Chapter 5, as the current density increases, the distribution of current through the thickness of a porous electrode becomes increasingly nonuniform (Figure 5.6). Assuming that the reaction products precipitate near where they are formed, there is the possibility that the pores in the front of the electrode will be filled before the discharge is complete. At best, the added capacity would not be used effectively. Therefore, increasing the thickness of the electrodes while maintaining a constant cell area is not recommended for large increases in capacity. This approach would only be chosen if the design fully accounted for the above effects or if the scaling factor were small, say 10–15%.

Another alternative, shown as Option 2 in Figure 8.4, is to keep the thickness of the electrodes and other cell components the same, and to increase the capacity by increasing the area of the cell. If the separator area is scaled with the capacity, Q, it follows that the volume scales by the same factor. What’s more, from Equation 8.14 the average current density is constant and electrochemical performance does not change appreciably. The resulting volume as a function of capacity is shown as O2 in Figure 8.5. The cell volume scales linearly with capacity, but is larger than the volume calculated for the previous case (Option 1). This is because the volume occupied by the separator and current collectors remained constant for Option 1, but scales with the capacity for the second option.

Can we continue to scale the capacity of the battery indefinitely by increasing its area? No, because other factors will eventually become important. One of these factors is the resistance associated with the two current collectors and their connection tabs as shown in Figure 8.6. This resistance, if important, can be reduced by increasing the thickness of the current collectors. Problem 8.7 explores the effect of scaling the thickness of the current collector by the cell area. This third option, shown as O3 in Figure 8.5, results in an even larger volume. However, it does lead to more confidence regarding cell performance.

Another alternative to increase capacity is to stack several electrodes or plates together in a single assembly. This configuration is shown in Figure 8.7 and represents a common approach used in both lead–acid and lithium-ion cells. The same electrode active material is placed on both sides of a current collector. This assembly is not a bipolar configuration—the individual electrodes or plates are electrically connected in parallel within a single cell. Additional plates with the same cross-sectional area are added to increase capacity. With the configuration shown in Figure 8.7, it is possible to keep the separator area and electrode thicknesses constant while varying the planform size independently by the addition or removal of plates to yield the desired capacity. The key differences between the configuration shown in Figure 8.7 and simply increasing the size of the electrode are manifest in the current collection, which avoids problems associated with large electrodes, and in planform size. Note that a single current collector serves two electrodes and will need to be sized accordingly. The use of plates to form a battery cell most closely represents case O2.

Finally, we have not considered the volume of the battery casing, tabs, and vents. Volume or mass package factors can range from 1.5 to 1.8. However, the volume of these ancillaries will not change the sizing principles discussed in this section.

Leave a Reply