The redox-flow battery is a battery in the sense that it is used to store and release energy. However, it operates much like a combination of a fuel cell (discharge) and an electrolyzer (charge). In contrast to typical secondary batteries where the reactants are part of the electrode, the reactants and products in a flow battery are contained within the electrolyte, which circulates through the cells. As we’ll see in a moment, this situation allows for decoupling of the power and energy requirements for the system. There are numerous possible redox couples; here we will focus on the vanadium system as an example.

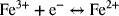

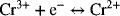

The vanadium redox-flow battery (VRB) employs two vanadium redox couples for the negative (V3+/V2+) and positive electrodes (VO2+/VO2+) as follows:

(14.26)![]()

Figure 14.16 illustrates how the system operates. A solution (anolyte) circulates through the negative electrode. A separate solution circulates through the positive electrode, the catholyte. Both solutions are acidic, and a proton exchange membrane is used to keep the solutions separate. During discharge, V(II) is oxidized to V(III) at the negative electrode. Electrons travel through the external circuit as usual, and the current in solution is carried primarily by protons. One mole of protons moves across the ion-exchange membrane for each mole of vanadium that is oxidized. These protons react with ![]() and electrons from the external circuit to form

and electrons from the external circuit to form ![]() and water according to Equation 14.27.

and water according to Equation 14.27.

As just mentioned, the negative and positive electrodes are separated by an ion-exchange membrane (see also PEM, Chapter 9) that prevents the mixing of electrolytes and allows for transport of protons between the electrodes. The ideal characteristics of this separator are low permeability to vanadium cations, high proton conductivity, as well as mechanical and chemical stability.

The electrochemical cell is sized to meet the maximum power [W] and voltage requirements. Independently, the energy requirement [W·h] can be accomplished simply by adding a larger storage tank for reactant-containing electrolyte. This decoupling is shown in Illustration 14.15.

ILLUSTRATION 14.15

A VRB energy storage system is to provide 1 MW of power for a period of 4 hours at 400 VDC. If a cell operates at 4 kA·m−2 and 1.23 V, determine the total cell area and number of cells in the cell stack. Next, calculate the size of the storage tanks. Assume a one-electron reaction and 1 M concentration for both electrodes.

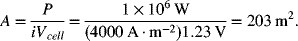

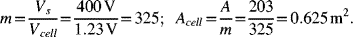

Cells are sized for power. First, estimate total cell area needed to satisfy power requirements:

The number of cells and individual cell size are

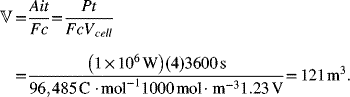

Tanks are sized to meet the energy requirements. The volume of each tank needed for a 4 hour capacity is

Note that the discharge time does not enter into the determination of cell area. Similarly, the volume depends on the product of power and time (energy) and is independent of the rate.

The analysis to find the relationship between current density and potential closely follows the developments made in earlier chapters for electrochemical cells. During discharge, the potential of the cell is the equilibrium potential minus the ohmic, kinetic, and concentration polarizations. Example charge and discharge curves are shown in Figure 14.17.

There are many ways to operate the system. It is instructive to write the equilibrium potential for the VRB. With activity coefficients neglected, the change in cell potential with reactant and product concentrations is clear.

(14.28)![]()

To minimize the volume of anolyte needed, we would like to convert nearly all of the V(II) to V(III). There are a couple of ways to effect this conversion. First, we could have the anolyte pass through the cells just once. Achieving full conversion would mean that the concentration of our reactant, V(II), would go toward zero at the exit of the cell. At that point, the equilibrium potential would drop and kinetic and mass-transfer polarizations would become very large. The negative effects associated with this approach could be mitigated to some degree by lowering the operating current density, but that would increase the size of the cell. A second option is to recirculate the anolyte as shown in the figure so that the reactants make many passes through the cell. The conversion during each pass is not high, but after many passes a high overall conversion is achieved. In the extreme, let’s imagine that we circulated so rapidly that the anolyte was always well mixed. In this instance, the cell polarizations are minimized but the equilibrium cell potential would change during discharge much like a battery does. These cases are explored further in the problems at the end of the chapter.

Just like other industrial electrochemical systems, economic considerations are paramount for redox-flow batteries. As such, the energy efficiency of the system is a critical metric. We can define efficiency as simply the ratio of the electrical energy out and the electrical energy in, sometimes called round-trip efficiency. If side reactions, crossover, and parasitic power are ignored, this can be approximated with the voltage efficiency of the charge and discharge process,

(14.29)

Using the data from Figure 14.17, we can estimate the current density required to achieve a round-trip efficiency of 65% to be about 2400 A·m−2 (1.35/2.09 = 0.65).

REDOX COUPLES FOR FLOW BATTERIES

The vanadium couple is only one of many that are possible for the redox-flow batteries. The key factor in commercialization of flow cells is, of course, economics, and here the cost of vanadium is quite high. The ideal couple would have

- Highly reversible reactions

- Earth abundant materials

- Low-toxicity

- Noncorrosive

- High solubility

- High equilibrium potential

Closure

Industrial electrolysis uses electrical energy to create desirable products via electrochemical processes. In this chapter, we considered several industrial processes of economic importance, including the production of chlorine and aluminum. We also applied the fundamental principles learned previously to help us understand the operation of electrolysis cells. Design criteria for electrochemical reactors were discussed and applied, and methods for approximating reactor size were demonstrated. The thermal management of industrial cells was also considered, with the help of an overall energy balance. Finally, we examined several ways in which electrochemical processes can be used to help achieve a sustainable future. As with any commercial product, economic considerations are critical and the cost of electricity often drives the feasibility of large industrial processes.

Further Reading

- Goodridge, F. and Scott, K. (1995) Electrochemical Process Engineering, Plenum, New York.

- Hine, F. (1985) Electrode Processes and Electrochemical Engineering, Plenum Press, New York.

- Muthuvel, M. and Botte, G. (2009) Trends in Ammonia Electrolysis: Modern Aspects of Electrochemistry. Springer, 45, 207–243.

- Newman, J. and Thomas-Alyea, K.E. (2004) Electrochemical Systems, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ.

- Pletcher, D. and Walsh, F.C. (1993) Industrial Electrochemistry, 2nd edn, Springer Science+Business Media, LLC.

- Rajeshwar, K. and Ibanez, J.G. (1997) Environmental Electrochemistry: Fundamentals and Applications in Pollution Sensors and Abatement, Academic Press, San Diego.

- Steckhan, E. (2012) Electrochemistry, 3. Organic Electrochemistry, Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Weinheim, Germany.

- Tobias, C.W. (1959) Effect of gas evolution on current distribution and ohmic resistance in electrolyzers. J. Electrochem. Soc., 106, 833.

Problems

14.1. What is the minimum energy required to produce a kg of NaOH from a brine of NaCl? Compare this number with typical values reported industrially of 2100–2500 Wh·kg−1. What are some factors that account for the difference? A rule of thumb for the chlor-alkali industry is that two-thirds of the production costs are electrical energy. If the cost of electricity is $0.06/kWh, estimate the cost to produce a kg of Cl2.

14.2. The third and most modern design for the chlor-alkali process uses an ion-exchange membrane instead of the porous diaphragm. The membrane allows cations to permeate through but is an effective barrier for anions and water. How would the cell design change for this approach? Identify possible advantages and disadvantages to the membrane design.

14.3. An alternative chlor-alkali process has been proposed. Rather than evolving hydrogen, the cathode for a membrane cell design is replaced with an oxygen electrode. Write the cathodic reaction at the oxygen electrode. Compare the equilibrium potential and theoretical specific energy for Cl2 production with that for the conventional cell. What are some advantages and challenges with this concept?

14.4. HCl (g) is a waste product in a number of chemical processes. Ideally, the HCl could be converted to Cl2(g) economically. There are several paths to do this conversion including the Deacon process, which is not electrochemical. You are investigating the direct conversion of anhydrous HCl in an electrochemical cell analogous to a proton exchange membrane fuel cell. A proton-conducting membrane serves as the separator and electrolyte. Write the overall and electrode reactions for this process. What is the equilibrium potential?

14.5. Calculate the theoretical specific energy (W·h·kg−1) to produce Al. Use the reaction shown in Section 14.5 at standard conditions. The U.S. Geological Survey provides the commodity price of Al, http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2012/5188/. If the energy efficiency of the process is 30%, what is the maximum price of electricity needed to make the process feasible?

14.6. An aluminum electrowinning process operates at 960 °C. At these conditions, the equilibrium potential is 1.22 V. If the cell is operating at 4.19 V with a faradaic efficiency of 92%, what is the energy efficiency of the process?

14.7. How much electrode area is needed to supply the world with Al? Use a production rate of 20 million metric tons per year. Assume the current density is 900 A·m−2 and a faradaic efficiency of 0.97. What is the annual release of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere? For comparison, in the United States, about 1.5 billion metric tons per year of carbon dioxide are emitted by the transportation sector.

14.8. During electrowinning of aluminum, some of the deposited material dissolves back into the melt. If the rate of dissolution is constant (x g·s−1), develop a relationship for the faradaic efficiency of the process as a function of current density, i. Do the experimental data in the table support this model?

| i [A·m−2] | ηf |

| 441 | 32.8 |

| 803 | 59.0 |

| 1190 | 71.9 |

| 5010 | 93.5 |

| 7520 | 94.6 |

| 9990 | 94.4 |

14.9. Use the parameters from Section 14.3 for the chlor-alkali cell to develop a polarization curve. If the total cost (installation and operating) is given by 0.01 Ac + 5 Vcell, at what current density are costs minimized?

14.10. A key advantage of the DSA for the chlor-alkali process is the removal of gas from the electrode gap. Consider an older design where the gas bubbles remain in the gap. Estimate the optimum electrode gap (minimum ohmic loss) for a 1 m long cell operating at 65 °C, 150 kPa, and 2500 A·m−2. If it were desired to keep the ohmic loss to less than 200 mV to achieve high-energy efficiency, at what current density would the cell need to operate? Use 0.5 mm for the bubble diameter.

14.11. A chlor-alkali plant has a capacity of 35,000 metric tons chlorine per year. If electricity costs are 0.06 [$·kWh−1], what are the annual savings and reduction in production costs per ton of chlorine for each mV of reduction in overpotential? Assume a faradaic efficiency of 0.95. The dimensionally stabilized anode (DSA) is able to reduce the overpotential by about 1 V at 10 kA·m−2. Does describing the DSA innovation as “one of the greatest technological breakthrough of the past 50 years of electrochemistry” seem justified?

14.12. For the diaphragm process shown in Figure 14.1, develop equations for material balances around the cell. Show how to relate the composition of the cathode liquor (caustic) to design parameters. Assume a production rate of 20 kg·h−1 chlorine per hour and that the feed is a saturated brine of NaCl. Include parameters for current efficiency, solubility of chlorine in the brine, and back diffusion of OH−.

14.13. A gas-evolving electrode operates with a gap of 4 mm and the height of the electrode is 0.5 m. The two-electron reaction with a gas-phase product takes place in an undivided cell (no separator) at an average current density of 200 A·m−2. The pressure is 150 kPa and the temperature is 35 °C. Use a bubble velocity of 6 mm·s−1. The conductivity of the solution is 5 S·m−1. It is proposed to reduce the gap to 2 mm to reduce ohmic losses. Is this a good idea? Explain your answer and include a sketch of the current distribution for the two cases.

14.14. For the following processes, indicate whether a divided cell is needed and why. Also indicate whether a bipolar configuration is feasible: (a) electrorefining of tin, (b) production of naphthoquinone (Illustration 14.10), (c) redox-flow battery, and (d) production of adiponitrile.

14.15. A monopolar cell for electrowinning of copper is an open tank that contains multiple parallel plate electrode pairs electrically connected in parallel. If the distance from cathode to cathode is 75 mm, the current density is 280 A·m−2, and the faradaic efficiency is 0.84, calculate the space–time yield. Why is there one more anode than cathode in the cell? Discuss any advantages that might result from making the anodes and cathodes slightly different sizes.

14.16. The cell for electrowinning of zinc is made up of 100 electrode pairs in a monopolar arrangement. Each electrode is 1.4 × 0.7 m. Given an electrode gap of 30 mm, and the i = 3000 A·m−2. The rate of flow of electrolyte is 120 m3·h−1, and enters the cell at a concentration of 100 kg Zn2+ m−3. How would you propose to flow electrolyte to the cells. Sketch the current density on the electrode. Why wouldn’t bipolar stack be practical for this application?

14.17. You are setting up a tank house for the electrowinning of Cu. The electrical supply is 180 VDC and 40 kA. For a 1 m2 cell operating at 300 A·m−2, the potential of the cell is 2.0 V and the faradaic efficiency is 85%. Using these conditions, how would you configure the tank house? If the equilibrium potential is 1.45 V, what is the energy efficiency of the process? The cathode cycle is 4 days, during this time by how much does the mass of the cathode increase? Assuming that the tank house operates 340 days per year, what is the annual production rate of copper?

14.18. A large tank house for the electrowinning of zinc contains 200 tanks, each containing 100 electrodes with an area of 1.3 m2 (both sides) in a bipolar arrangement. The electrolyte is acidic. If the operating current density is 490 A·m−2, and the cell potential is 3 V, what is the steady-state cooling requirement for the tank house? If the rate of flow of electrolyte through the cells is 4800 m3·h−1, estimate the change in temperature of the electrolyte through the tank house. Use the heat capacity and density of pure water for this calculation.

14.19. An alternative to the carbon anode in the electrowinning of aluminum is the so-called inert anode. The cathode reaction is unchanged, but here oxygen is evolved instead of consumption of carbon. Write the overall reaction for the inert process. Compare the standard potential for the reaction with the reaction from Equation 14.13. The Hall–Héroult process is already notoriously inefficient. What then are the possible advantages of the inert-anode process?

14.20. Consider the wastewater cleanup with porous electrodes shown in Illustration 14.14. If the particle size were increased to 2 mm, to what value would the effective conductivity need to be increased in order to keep the Hg within the limits. Use an area of 0.75 m2.

14.21. Lithium metal is produced using an electrolytic process. The electrolyte is LiCl-KCl eutectic melt at 427 °C. At these operating conditions, the equilibrium potential is 3.6 V. What is the cathodic reaction? The faradaic efficiency for lithium is reported to be 95%, and the energy consumption is 35 kWh·kg−1. At what potential is the cell operating? What is the energy efficiency of the cell?

14.22. The growth in the lithium-ion battery market has raised demand for lithium. Rechargeable batteries typically use lithiated metal oxides, and the precursor is LiOH not lithium metal. Describe a method to produce LiOH by a process similar to that used for caustic soda using an ion-exchange membrane.

14.23. Calculate the power needed to produce 100 million kg·yr−1 of adiponitrile. Assume the faradaic efficiency is 95% and that the cells operate at a potential of 4.6 V.

14.24. A plant produces 20,000 metric tons of adiponitrile per year. If the power requires is 50 MW, calculate the specific energy (kWh·kg−1) and energy efficiency of the process assuming a faradaic efficiency of 90%. Use 3.08 V for the equilibrium potential of the reaction. How might hydrogen evolution be avoided?

14.25. Compare the energy efficiency of the alkaline electrolyzer from Illustration 14.13 with the efficiency that you would achieve if the current density were doubled and the voltage of the cell increased to 2.25 V. Look at energy efficiency and space–time yield.

14.26. Electrolyzers and fuel cells are envisioned to be a part of an energy storage system for the electrical grid. When supply exceeds demand, hydrogen is generated and stored. When demand exceeds supply, this stored hydrogen is used in a fuel cell to generate electricity. Using the efficiency for electrolysis from Illustration 14.13 and assuming a fuel-cell system efficiency of 60%, what is the round-trip efficiency?

14.27. Calculate change in equilibrium potential as a function of SOC for vanadium redox-flow battery. Assume that the junction region is an ion-exchange membrane that only allows transport of water and protons and completely excludes anion and vanadium ions.

14.28. An iron–chromium redox-flow battery energy storage system is to provide 8 MW of power for a period of 3 hours at a minimum of 650 VDC. The two reactions are

- What is the standard potential of the full cell?

- Assume that the potential of the cell can be treated as ohmically limited. Using the equilibrium potential calculated in part (a) and a resistance of 0.05 mΩ·m2, what cell area is required to provide the desired power while maintaining a round-trip efficiency of 80%? Assume that the current density is the same for charging and discharging.

- If it is impractical to have single cells with an area of greater than 1 m2, what series–parallel configuration would you recommend?

- What is the total volume of electrolyte needed if the solubility of reactants is 0.7 M?

14.29. For the system shown in Illustration 14.15, calculate the rate of heat removal required to maintain a constant temperature. Use a utilization of 0.8 for both the anolyte and the catholyte. The heat capacity can be approximated as that of water. Equation 7.20 can be used to estimate the rate of heat generation.CopycopyHighlighthighlightAdd NotenoteGet Linklink

Leave a Reply