In contrast to the battery, a fuel cell is typically a steady-state device. As such, the fuel and oxidant are supplied continuously. In the previous chapter, we focused on the electrochemistry of the fuel cell. Now we will examine the entire fuel-cell system. Many cells are combined to form a cell stack assembly (CSA), which is the “heart” of the fuel-cell system. In addition to the cell stack, there can be considerable equipment associated with the proper operation of the system. Figure 10.1 shows a highly simplified arrangement, which will serve to illustrate the main points. Here, the system is divided into three parts: a fuel processor, a cell stack, and a power conditioning section.

As mentioned previously, the oxidant, typically air, must be supplied continuously to sustain the electrochemical reaction at the cathode. Therefore, a compressor or air blower is used to provide the required flow of oxidant. Higher air flow rates lead to a reduction in the polarization at the cathode, but high air flow rates are not always preferred. The optimal flow rate will depend on the type of fuel cell and the application for which it is used. In all cases, some of the power generated in the cell stack must be used to operate the compressor or blower, impacting the efficiency of the system.

Similarly, fuel is supplied constantly to the anode. For many fuel-cell systems, the fuel must be processed prior to entering the electrochemical device. Operation on pure hydrogen is relatively simple, but use of a hydrocarbon fuel may require sulfur removal, reformation of the fuel (discussed below), and in some cases even the removal of small amounts of carbon monoxide from the reformed fuel. Here, we consider natural gas as the fuel for a low-temperature PEM fuel cell. After sulfur removal, three steps are needed to process the fuel.

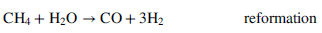

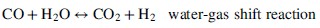

Reformation is a general term that refers to the conversion of a hydrocarbon fuel to hydrogen and carbon monoxide. Reformation is an endothermic reaction; therefore, heat must be added to drive the reaction. Ideally, reforming is done with close thermal coupling of the chemical (reformation) reactor with the fuel-cell stack in order to use waste heat from the stack to drive the chemical reaction. If the amount or quality of heat available is not sufficient, then some of the fuel may be burned to assist with reformation. Any combustion of the fuel to provide heat will, of course, reduce the efficiency of the system. Reformation is performed at high temperatures. Although some of the CO reacts with water to form hydrogen at the high temperature, a second lower temperature reactor is often needed to shift the equilibrium further toward hydrogen production. Finally, for acid fuel cells below about 150 °C, the remaining carbon monoxide must be removed before delivering the hydrogen to the cell stack. Removal is accomplished by selective oxidation of the carbon monoxide.

As we saw in Chapter 9, a general characteristic of a fuel cell is that the efficiency is highest at low current densities. Efficiency will be considered in greater detail in the next section, but one cannot design a fuel cell with efficiency as the only target. System size, cost, and durability are also important design considerations. Referring back to Figure 10.1, the efficiency of a fuel cell can be expressed as the net electrical work produced divided by the energy available from the reactants:

(10.1)

where the free energy change at standard conditions has been used to approximate the free energy change of the system. This is a reasonable assumption since it is likely that streams entering and leaving the overall system will be close to standard conditions. The gross electrical work is simply the current multiplied by the operating potential of the cell stack, ![]() . From this value, we subtract any power needed to run ancillary equipment, also called parasitic power, as well as any electrical losses external to the stack (e.g., losses resulting from power conditioning). Clearly, we want the cell potential to be high in order to achieve high efficiency. Thus, minimization of ohmic, kinetic, and mass-transfer polarizations is desired, just as it was for batteries.

. From this value, we subtract any power needed to run ancillary equipment, also called parasitic power, as well as any electrical losses external to the stack (e.g., losses resulting from power conditioning). Clearly, we want the cell potential to be high in order to achieve high efficiency. Thus, minimization of ohmic, kinetic, and mass-transfer polarizations is desired, just as it was for batteries.

The fuel can be thought of as a compound containing carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, generically represented with the formula CxHyOz. We have already seen some examples of fuels, CH3OH, CH4, and H2. When calculating the energy content or availability of the fuel, we assume that all of the fuel supplied to the fuel cell reacts completely to form water and carbon dioxide,

This reaction describes the combustion of the fuel; but remember, a fuel cell is not a thermal device. The maximum work per time available from the reactants is given by the change in Gibbs energy for the reaction (10.2) multiplied by the flow rate of the fuel. Ideally, the flow of oxidant would be the exact stoichiometric amount needed for complete combustion of the fuel. It turns out that complete stoichiometric utilization of the fuel is not practical. Rather, reduction of the required fuel flow rate and optimization of the oxidant flow rate represent important design considerations.

For fuel cells, a system efficiency based on the change in enthalpy is more commonly used than the definition above in terms of the Gibbs energy. The enthalpy-based efficiency is called the system thermal efficiency, and its use in electrochemical systems is limited mostly to fuel cells. In defining this system efficiency, we assume that water and carbon dioxide are produced according to the stoichiometry of Equation 10.2. Since the enthalpy of formation of molecular oxygen is zero,

The denominator here is the change in enthalpy associated with combustion of the fuel, also termed the heating value of the fuel. In order to calculate the heating value, one must decide whether to treat product water as a vapor or as a liquid. The enthalpy of reaction depends strongly on the phase of the product water. The higher heating value (HHV) assumes that the product water is in the liquid phase; the lower heating value (LHV) assumes it is in the vapor phase. Usually, the lower heating value is used, regardless of the actual state of the water. Can you infer why someone promoting fuel cells might adopt this practice? Ideally, the enthalpy change would account for actual temperatures of the inlet and outlet streams. However, for our purposes, we will assume that the heat of reaction at 25 °C can be used to adequately approximate the required heating value. The system thermal efficiency is illustrated in the following example.

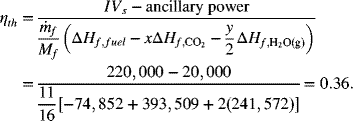

ILLUSTRATION 10.1

A fuel-cell system uses natural gas as the fuel. The gross electrical output is 220 kW, the ancillary power is 20 kW. Neglect any electrical and power conditioning losses. If methane is fed to the fuel-cell system at a rate of 0.011 kg s−1, what is the system thermal efficiency?

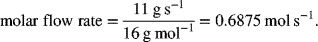

The net electrical output is simply 220 − 20 kW =200 kW. The mass flow rate of 0.011 kg s−1is converted to a molar flow rate, using the molecular weight of 16 g·mol−1 for methane.

The enthalpy of formation for methane, water (vapor), and carbon dioxide are found in Appendix C and are used to find the efficiency. For methane, x = 1, y = 4.

Note that we used the thermodynamic data at 25 °C. How can this be justified? Although the cell may be operating at a much higher temperature, it is likely that the air, fuel, and even exhaust of the complete system won’t be far away from these temperatures.

We can write the system thermal efficiency as the product of the fuel efficiency, thermal voltage efficiency, power-conditioning efficiency, and mechanical efficiency:

The first term on the right side of Equation 10.4 is the fuel efficiency. It is defined as the fraction of the fuel fed into the system that contributes to the electrical current in the fuel cell. Ideally, this would be one, but that is difficult to achieve.

where ![]() is the flow rate through a single cell and

is the flow rate through a single cell and ![]() is the combined flow rate through all of the cells in the stack. Take a moment and think about the term (4x + y − 2z). You should be able to relate this to the number of electrons being transferred per mole of fuel (see Equation 10.2). It may be helpful to think about this in terms of the moles of O2 required per mole of fuel and the number of equivalents associated with the reduction of each mole of O2.

is the combined flow rate through all of the cells in the stack. Take a moment and think about the term (4x + y − 2z). You should be able to relate this to the number of electrons being transferred per mole of fuel (see Equation 10.2). It may be helpful to think about this in terms of the moles of O2 required per mole of fuel and the number of equivalents associated with the reduction of each mole of O2.

Next is the thermal voltage efficiency, which describes how effectively the energy from the fuel is converted to electrical power in the fuel cell. This efficiency accounts for voltage losses in the cell; any voltage losses or cell polarizations, explored in Chapter 9, reduces this efficiency. Here, ηV,t is defined as the operating potential of the cell divided by the change in enthalpy of the reaction expressed in [J·C−1]:

We can also express thermal voltage efficiency in terms of the voltage efficiency for fuel cells introduced in Chapter 9:

Note that the voltage efficiency defined here for a fuel cell, ![]() , is slightly different from the voltage efficiency used for batteries, Equation 7.22. The thermal voltage efficiency is obtained by multiplying

, is slightly different from the voltage efficiency used for batteries, Equation 7.22. The thermal voltage efficiency is obtained by multiplying ![]() by the ratio of changes in Gibbs energy and enthalpy. Because we have defined this thermal voltage efficiency in terms of enthalpy instead of Gibbs energy, the efficiency is not unity, even for reversible conditions.

by the ratio of changes in Gibbs energy and enthalpy. Because we have defined this thermal voltage efficiency in terms of enthalpy instead of Gibbs energy, the efficiency is not unity, even for reversible conditions.

For fuel-cell systems, efficiencies are defined in terms of the change in enthalpy rather than the change in Gibbs energy. This convention is largely historical. Other methods of producing electricity from fuels use thermal engines that are limited by the Carnot efficiency, where the heat released by the combustion of fuels is important.

The gross electrical power produced by the stack generally requires conditioning, converting DC power to regulated AC power for instance. The efficiency for power conditioning is expressed as

(10.8)

These losses may also come from electrical resistances in the cables and contact resistances, as well as losses from the power conversion. Finally, a mechanical efficiency is defined as

(10.9)

Here, the net electrical power is the ancillary power subtracted from the conditioned power. Thus, we see that as the power required to drive any pumps or blowers to operate controllers or other devices in the system is reduced, the mechanical efficiency approaches unity.

The flow of power is depicted in Figure 10.2. Each of these efficiencies will be used over the course of the chapter. In particular, we are interested in how they are interrelated and influenced by the system design.

Leave a Reply