Electrolytic Fuel Generation

As we look to the future, it seems clear that the sun will be our primary source of energy. In addition to solar thermal methods, solar energy can be captured in the form of energetic electrons and holes, inherently an electrochemical process. Also, since the availability of solar energy is cyclic, electrochemical processes can be used for energy storage in order to provide the energy needed in off cycles.

Perhaps more important, the transition to solar energy as the primary source of energy for society will likely be accompanied by a shift from fuel-based energy use to direct use of electricity. Electrochemical devices will undoubtedly play a critical role in this shift. Electricity has traditionally been the “high-end” form of energy since it has most frequently been generated using fuels. Consequently, it has historically been more efficient to use fuels directly, where possible, rather than to use fuels to generate electricity, which is subsequently used for the intended application. This will change as electricity is generated directly from renewable sources; hence, electrochemical processes that use electricity directly will have an added economic advantage. There will also likely be a shift from centralized generation of electricity to a distributed solar-based system, which will again impact the use and scale of electrochemical devices. The same type of shift is already occurring in the transportation industry, driven by environmental concerns, where portability will continue to depend on electrochemical devices.

What role, if any, will electrolytic processes play with respect to fuels in a solar-based system? In applications where direct use of electricity is not viable, electric power can be used to generate solar fuels such as hydrogen. This process is a reversal of the previous paradigm where fuels were used to generate electricity. Electrolysis of water to produce hydrogen and oxygen is perhaps the electrolytic process first considered for fuel generation.

Water Electrolysis

The electrolysis of water is essentially a fuel cell in reverse, where electricity is used to create hydrogen and oxygen from water. Therefore, water electrolyzers reflect the types of technologies that we considered for fuel cells in Chapter 9. The three principal types of electrolyzers are alkaline, PEM, and solid oxide.

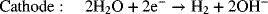

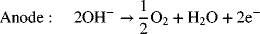

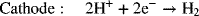

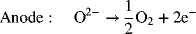

Most commercial water electrolysis is performed with alkaline electrolyzers. The electrode reactions are as follows:

and

The net reaction is, of course, just the splitting of a water molecule to produce hydrogen and oxygen. Figure 14.13 shows the equilibrium potential and thermoneutral potential (−ΔHRx/nF) for water electrolysis as a function of temperature. These data assume the water is a vapor. Near room temperature, where water is a liquid, the two values are close to one another. At high temperatures, there is large difference—which is important for high-temperature electrolysis. The equilibrium potential, which is proportional to the free energy change for the reaction and, therefore, the minimum potential needed to split the water, decreases with increasing temperature. In contrast, the thermoneutral potential does not change significantly with temperature. Operation at a cell voltage greater than the equilibrium potential but less than the thermoneutral potential would lead to net cooling due to the reversible heat term (TΔS) for water electrolysis, and would require the addition of heat to the reactor. Above the thermoneutral potential, the irreversible losses in the cell are sufficient to generate the heat needed for the reaction. Note that, while convenient, analysis with the thermoneutral potential is approximate for an open system such as an electrolyzer since it does not account for the enthalpy of the inlet and outlet streams. Therefore, where possible, use of the full energy balance, Equation 14.22, is preferred.

Voltage losses as a function of current density in a typical alkaline electrolyzer are shown in Figure 14.14. The overpotentials for both the anodic and cathodic reactions are significant. As expected, ohmic losses become more important at the higher current densities. Since the energy efficiency is a direct function of the operating voltage, a trade-off exists between the absolute amount of hydrogen that can be produced in a given electrolyzer and the energy efficiency at which it can be produced. Commercial electrolyzers typically operate at cell potentials below 2 V and current densities between 1000 and 3000 A·m−2. Note that at 25 °C, Uθ = 1.229 V and the thermoneutral potential is 1.481 V (assuming liquid water). Given the relatively sluggish kinetics at these temperatures, operation below the thermoneutral potential is not practical.

Both monopolar and bipolar alkaline electrolyzers are available, although the bipolar configuration is more common. The electrolyte consists of 25–30 wt% KOH, which has a relatively high electrical conductivity. The decision to operate at high rather than low pH is based on material’s cost and stability. Specifically, corrosion problems are less severe at high pH than under acidic conditions. Cells traditionally operate at temperatures ranging from 65 to 100 °C. Input or makeup water must be relatively pure (κ < 500 μS·m−1) in order to avoid the buildup of impurities in the cell. Alkaline electrolyzer technology is considered to be mature with a life expectancy of up to 15 years. High-temperature alkaline cells have also been developed; these cells operate at temperatures up to 150 °C in order to improve conductivity and reaction kinetics, although water management is an issue at the high temperatures.

ILLUSTRATION 14.13

Efficiency of an Alkaline Water Electrolyzer

A bipolar alkaline water electrolyzer is operated at 80oC and consumes 100 kW during operation. The voltage between each anode and cathode is 1.85 V, and the corresponding equilibrium voltage at the operating temperature is 1.18 V. The current density is 1500 A·m−2 (assume uniform) and the faradaic efficiency is 98.5%. The electrodes are 1 m2. Please determine the operating current and voltage of the stack, the number of cells in the stack, the rate of hydrogen production, the energy efficiency of the electrolyzer, and the specific energy for hydrogen production (kWh·Nm−3, where Nm3 is a “normal” m3 at 0 °C and 100 kPa).

Operating current: (1500 A·m−2)(1 m2) = 1500 A.

Stack voltage: ![]() .

.

Number of cells: ![]() .

.

Rate of H2 production:

Use the ideal gas law to determine the volumetric flow rate of hydrogen.

Use normal volume of hydrogen (Nm3): ![]() .

.

Specific energy consumption: ![]() .

.

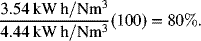

Energy efficiency (percent of energy consumed that results in hydrogen production): ![]() .

.

An efficiency based on the HHV of hydrogen gas ![]() is also sometimes reported,

is also sometimes reported,

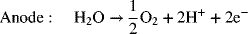

Water electrolyzers based on proton exchange membranes (PEM) are also manufactured. These electrolyzers first appeared during the Space Race in the 1960s, and use technology similar to that of PEM fuel cells. The electrode reactions are as follows:

Hydrogen production rates in PEM electrolyzers are low relative to alkaline cells, in spite of the fact that the current densities are higher. The low production rate is due to the smaller electrode surface area (superficial) in the cell. Use of an ion-exchange membrane provides enhanced safety and increased purity due to the low gas permeability of the membrane. PEM electrolyzers operate well at partial load and have good dynamic performance. The major disadvantages of these electrolyzers are higher initial cost due to the membrane and catalysts, shorter lifetimes, and lower hydrogen production capacity.

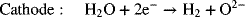

A promising technology for water electrolysis that is still at the research stage is that of solid oxide electrolyzers (SOEs). Analogous to solid oxide fuel cells, these devices operate at high temperature and utilize a solid, ceramic O2− conducting electrolyte. The reactions are as follows:

Operation at temperatures up to 1000 °C provides some important advantages. Reaction rates are much faster at high temperature, which circumvents the need for expensive catalysts. Also, the equilibrium voltage decreases with increasing temperature—at 1000 °C U = 0.922 V. That means that less electrical power is needed to drive the reaction in the desired direction to produce hydrogen and oxygen. As seen in Figure 14.13, at 1000 °C, the thermoneutral potential is 1.291 V. It is easy to conceive of a condition where the cell potential is below the thermoneutral potential. This means that, if available, high-temperature heat rather than electricity could be used to provide some of the energy needed to carry out the reaction. Consequently, these SOEs are viewed as a candidate for coupling with high-temperature gas-cooled nuclear reactors to provide both the electrical energy and high-temperature heat for optimal operation. SOEs also provide the advantage of fuel flexibility since, for example, they are capable of directly reducing CO2 to CO or a combination of H2O and CO2 to syngas (H2 and CO) if desired. The primary concern with SOEs is the lack of suitable materials to provide the lifetime needed for industrial applications.

In spite of recent and continuing developments, water hydrolysis is still more expensive, in general, than hydrogen generation from hydrocarbon sources. Consequently, only about 4% of hydrogen is currently produced from water. The largest electrolytic hydrogen plants worldwide are located in proximity to hydroelectric generation facilities in order to take advantage of inexpensive off-peak power.

Other Electrolysis Processes

There are several other electrolytic processes that may offer advantages over water electrolysis. Two key advantages include: (1) use of a waste stream to produce the desired fuel and perhaps other valuable products while simultaneously cleaning up the stream and (2) reduction of the voltage, and hence the energy, required for hydrogen production. It may also be possible to design or modify processes that have traditionally treated hydrogen as an undesirable by-product to produce hydrogen as one of the intended products. Two examples of alternative processes for hydrogen generation include the electrolysis of HCl and the electrolysis of NH3.

Waste streams rich in ammonia can be treated by electrolysis to produce hydrogen gas while simultaneously cleaning up the stream. The equilibrium potential for the electrolysis cell is 0.06 V, much lower than that for water electrolysis (1.229 V). Thus, hydrogen production from ammonia waste streams would require much less energy than that required for water electrolysis. In a similar fashion, urea-contaminated wastewater can also be treated by electrolysis (U = 0.37 V). In addition, both of these processes contribute in a positive way to the reduction of the amount of fixed nitrogen, which has increased significantly as a result of human activity. Finally, another electrochemical process for hydrogen production involves the use of a photoelectrochemical cell. This process will be treated separately in Chapter 15.

Wastewater Treatment

Several of the processes just mentioned involve the use of electrochemical reactors in environment friendly ways to produce useful products while simultaneously cleaning up waste streams. Another use of electrochemical technologies is for the cleanup of industrial effluent streams containing dilute concentrations of toxic materials. To illustrate, electrochemical methods can be used to remove toxic metal ions and have been the subject of renewed interest as regulations have been tightened. For many metals, it is no longer feasible to meet the specified limits for effluent discharge with use of conventional hydroxide precipitation methods. Also, the cost of disposing of the precipitation sludge has increased dramatically as such disposal must ensure that ground contamination by leaching out of the metal ions does not occur. In addition, remediation of water pollution caused by low concentrations of pharmaceutical residues is of significant recent interest and can be done electrochemically. In the treatment below we assume the following:

- The concentration of the contaminant is dilute. Therefore, removal of the contaminant does not change the liquid flow rate to any appreciable extent.

- The removal or cleanup of the contaminant is mass-transfer limited.

- The inlet flow rate and concentration are known.

- The outlet target concentration is known (typically set by regulation).

- Operation is continuous and steady state.

- The reactor cross section is constant and variations only occur in one dimension along the length of the reactor.

- Axial diffusion is not significant.

- Excess supporting electrolyte is used to enhance the conductivity and reduce the potential drop in solution.

The situation that we consider here involves a three-dimensional porous electrode. Our objective is to estimate the size of reactor needed to clean up the stream to the desired level. The flow-through and flow-by configurations, as well as the required material and charge balances, were presented in Chapter 5. Key results are repeated here for convenience. The concentration distribution under mass-transfer control is a function of x only:

where vx is the actual velocity of the fluid in the pores in the direction of interest (εvx would be the superficial velocity). Even though the local rate of reaction is controlled by mass transfer, current must still flow in solution between the upstream counter electrode and the three-dimensional electrode of interest. Again, as we saw in Chapter 5, the current in solution is

(5.60)![]()

Finally, there is a potential drop in solution associated with the current flow. We consider the most common situation where σ ≫ κ. Under such conditions, the change in overpotential is equal to the change in the potential in solution across the thickness of the electrode.

where ![]()

You may be wondering why we care about the potential drop and change in overpotential if the system is at limiting current and controlled by mass transfer. To illustrate, consider Figure 14.14, which shows the current density as a function of overpotential. At limiting current, the current does not change with changing overpotential. However, if the overpotential is increased too much, the current will again increase due to side reaction(s). Side reactions should be avoided since they consume power and may have significant additional negative impacts on the process. For the process under consideration, side reactions are avoided by limiting the potential drop in solution, which limits the range of overpotentials in the system. The maximum ![]() depends on the specific chemical system, but is usually between 100–300 mV. Equation 5.62 can be rewritten as

depends on the specific chemical system, but is usually between 100–300 mV. Equation 5.62 can be rewritten as

where the superficial velocity, vs = ![]() /Ac. Equation 5.57 can be used to relate the concentration at the outlet to the thickness L of the electrode as follows:

/Ac. Equation 5.57 can be used to relate the concentration at the outlet to the thickness L of the electrode as follows:

In writing the equation in this form, we recognize that kcm is a function of the velocity through the bed, vx, which will vary with both ![]() and Ac. The following correlation from Wilson and Geankoplis for packed beds at low Re can be used:

and Ac. The following correlation from Wilson and Geankoplis for packed beds at low Re can be used:

This correlation applies to a packed bed of spherical particles: 0.0016 < Re < 55, 168 < Sc < 70,600, and 0.35 < ε < 0.75. Mass-transfer coefficients in electrochemical reactors typically vary between 10−6 and 10−4 m·s−1.

Our goal is to perform a preliminary calculation of the size of the flow-through reactor. In doing so, we note that there are multiple combinations of cross-sectional area and length that will provide the desired outlet concentration. Also, the simple model used here seems to indicate that the length of the porous bed should be as short as possible since a short length would minimize the potential drop and the pressure drop through the bed (Figure 14.15). However, practical issues such as the nonuniformity of current across a large area and the difficulty of fabricating and obtaining uniform flow over a thin bed with a large cross section become important. Where possible, we recommend that a cross-sectional area consistent with a commercially available electrolyzer be chosen in order to avoid the design and fabrication of a custom system. In practice, the final design decisions will be based on an optimal return on investment.

The preliminary design calculation can be performed as follows:

- Choose an initial cross-sectional area for the reactor (best if aligns with that of a commercial available reactor).

- From the total flow rate, cross-sectional area, and void fraction, calculate vs and vx.

- Use vx to estimate kc for the bed with use of a correlation or from experimental data.

- Calculate the length L of the bed with use of Equation 14.24.

- Repeat the above steps for several possible values of the cross-sectional area until a value for L that is comparable to that of the height and width of the unit is obtained.

- Use Equation 14.23 to check if the maximum potential drop has been exceeded for the chosen value of L.

- If the absolute value of the potential drop is lower than the specified maximum, the initial sizing of the electrolyzer is complete. If the potential drop is too high, increase the cross-sectional area until the potential drop no longer exceeds the specified maximum.

Illustration 14.14 demonstrates this general procedure.

ILLUSTRATION 14.14

Removal of Hg from a dilute product waste stream. A stream containing 4 ppm by weight of Hg is to be cleaned to an outlet concentration of 0.05 ppm with use of a particulate flow-through electrode. The flow rate of the stream is 20 m3·h−1. The packed bed is 45% porous and is made from particles that are 1 mm in diameter. The effective conductivity of the electrolyte is 10 S·m−1, significantly lower than the electrical conductivity of the solid bed. The removal reaction is cathodic, and the anode is located upstream from the porous electrode. Please determine the size of the porous bed needed to carry out the desired reduction in Hg concentration. The maximum potential drop across the 3D electrode is 200 mV. The diffusivity of the soluble Hg species is 0.7 × 10−9 m2·s−1. Assume a two-electron process.

SOLUTION:

Initially, we choose Ac = 1m2 as this size is frequently used in practice.

The superficial velocity is: vs = ![]() /Ac = (20 m3·h−1)/(1m2) = 20 m·h−1 = 0.0056 m·s−1

/Ac = (20 m3·h−1)/(1m2) = 20 m·h−1 = 0.0056 m·s−1

Using ρ = 997 kg·m−3, μ = 0.89 mPa·s, we find that Sc = 1276, and Re = 6.22; therefore, from Equation 14.25,

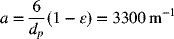

The specific area of the bed can be approximated from the particle size assuming spherical particles:

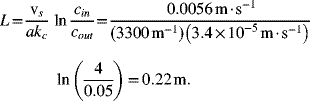

We can now calculate the length of the bed:

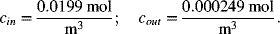

Note that the units on the concentration do not matter for this calculation as long as the ratio is accurate. However, concentration in mol·m−3 is needed to check the potential drop. The values of the concentration are

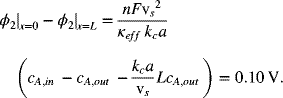

We can now check the potential drop in solution:

This value is smaller than the specified maximum. Therefore, these dimensions are acceptable.

| Ac [m2] | L [m] | Δϕ [V] |

| 1 | 0.22 | 0.10 |

| 0.75 | 0.27 | 0.16 |

| 0.5 | 0.35 | 0.32 |

Noting that L is a bit smaller than the height and width (assuming a square cross section), it should be possible to reduce the cross-sectional area and increase the thickness. The table provides a summary of values considered.

Examination of these values shows that L cannot be increased substantially without reaching the voltage limit of 0.2 V. In this case, one would look for a commercial reactor whose cross section is about 0.75 m2.

Leave a Reply