Fluid flow is sometimes used with porous electrodes in order to bring reactants and products in and out of these high-surface-area electrodes. A number of different flow configurations are possible. Two basic categories are the flow-through and flow-by configurations (Figure 5.14). In the flow-through arrangement, the fluid flow is parallel to the current flow, and the fluid flow actually flows through the current collector. In the flow-by configuration, fluid flow is perpendicular to the current flow. Also shown in Figure 5.14b is a gap between the electrodes. In cases where it is not desirable to mix the two reactant streams, a porous or membrane separator may be used.

One important application for flowing systems is the removal of low concentrations of valuable metals or contaminants by electrochemical deposition or reaction. We will consider the mass-transfer limited deposition of a metal, such as copper in a supporting electrolyte, where the flow and the current are in the same direction (flow-through configuration). The analysis is performed for the cathode (−) where the anode (+) is assumed to be upstream as shown in Figure 5.15.

Because of the supporting electrolyte, it is not necessary to include the migration term in the flux equation (see Section 4.3). The flow velocity is controlled independently and is assumed to be constant. The mass-transfer coefficient is taken to be a function of the flow rate only, and is therefore constant for this analysis. Plug flow is assumed so that the problem is one dimensional, and changes occur only in the direction of the flow. With these assumptions, the flux equation for the species of interest becomes

where vx is the velocity of the fluid in the pores in the direction of interest (εvx would be the superficial velocity). As before, this flux is based on the superficial area of the electrode perpendicular to flow direction. For simplification, we further assume that axial diffusion is small relative to convective transport, which leaves us with just the second term on the right side of Equation 5.54. At limiting current, the potential and concentration fields are decoupled, and we can solve the material balance directly for the concentration profile of species A in the electrode. At steady state, the material balance is (see Equations 5.8 and 5.9)

(5.55)![]()

where a mass-transfer expression has been used to describe the species reaction rate at the surface, jn. The concentration at the pore surface is, of course, equal to zero at limiting current, and this fact has been accounted for in the above equation. This expression can be integrated along the direction of flow to yield the concentration profile with use of the following boundary condition:

(5.56)![]()

to yield

If we assume that the desired reaction is the only reaction that takes place in the electrode, we can solve the charge balance to obtain the current and potential distributions. The charge balance is

Integration followed by application of the following auxiliary condition:

(5.59)![]()

yields the expression for the superficial current density,

Examining this equation, we see that the current in solution is directly related to the amount of A that reacts. Specifically, the total current at the front of the electrode (x = 0) is equal to the difference between the amount of A that enters the electrode and the amount that leaves the electrode, multiplied by nF. As L → ∞, essentially all of the A is reacted in the electrode and the current reaches its maximum value of ![]() . However, the utilization of the electrode drops as the electrode thickness increases beyond the point at which almost all of A has reacted. Further increases in thickness do not increase the current but result in increased pumping costs and a larger initial capital investment because of the thicker electrode.

. However, the utilization of the electrode drops as the electrode thickness increases beyond the point at which almost all of A has reacted. Further increases in thickness do not increase the current but result in increased pumping costs and a larger initial capital investment because of the thicker electrode.

ILLUSTRATION 5.5

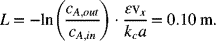

A packed bed electrode is used to remove metal ions from solution. The inlet concentration of the metal ions in a supporting electrolyte solution is 0.002 M, and the desired outlet concentration is 0.0001 M. The size of the electrode perpendicular to the flow is 25 cm × 25 cm, and the volumetric flow rate of the solution to be treated is 25 L·min−1. The spherical particles that make up the bed are 0.5 mm in diameter. The porosity of the bed is 0.45, and the mass-transfer coefficient is 0.003 cm·s−1. The direction of flow is from the front of the electrode toward the back, similar to that seen in Figure 5.15. The reduction reaction is a two-electron reaction. Please calculate (a) the required thickness of the electrode, (b) the superficial current density at the front of the electrode closest to the anode, and (c) the relative rates of reaction at the front and back of the electrode.

SOLUTION:

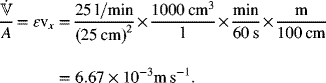

Part (a) can be addressed with Equation 5.57. The value of the mass-transfer coefficient was given in the problem statement. However, we need values for the velocity and a, the area per volume. The superficial velocity is

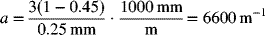

We can use Equation 5.15 to estimate a for a packed bed of spherical particles:

From Equation 5.57 for x = L,

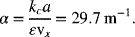

For part (b), we first determine α:

We then use Equation 5.60 at x = 0:

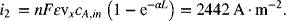

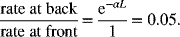

For part (c), the local reaction rate is proportional to exp(-αL), as seen in Equation 5.58. Another way of looking at this is to realize that the local reaction rate is directly proportional to the local concentration, which varies exponentially through the electrode. Therefore, for this example,

This is also equal to ![]() . Therefore, the rate at the back of the electrode is only 5% of that at the front. That number would decrease exponentially with increasing L.

. Therefore, the rate at the back of the electrode is only 5% of that at the front. That number would decrease exponentially with increasing L.

In the above treatment, side reactions were not considered. What is the impact of such reactions? To address this question, let’s consider perhaps the most straightforward example of a side reaction, hydrogen evolution at cathodic potentials. If the cathodic overpotential becomes too large, hydrogen evolution may dominate over the desired reaction. Thus, there is a practical limit to the potential drop that is permitted across the electrode. The overpotential must be sufficiently large to drive the desired reaction, but not so large that side reactions prevent the desired reaction from occurring. The range of overpotentials at which limiting current conditions prevail is roughly 0.1–0.3 V, depending on the system. Beyond this, the current increases due to side reactions. This means that the change in overpotential across the thickness of the electrode cannot vary by more than this amount without appreciable side reaction.

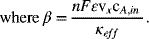

The most common situation is where σ ≫ κ. Under such conditions, the change in overpotential is equal to the change in the potential in solution across the thickness of the electrode. To estimate the change in potential, we can substitute Ohm’s law into Equation 5.60, using the effective conductivity of the supporting electrolyte, and integrate to yield the following expression for the potential:

(5.61)![]()

The total potential difference across the electrode is

The maximum value occurs for electrodes of large thickness, where Equation 5.62 simplifies to

and ![]() is the superficial velocity. For comparison, if we substitute for the values from the illustration above,

is the superficial velocity. For comparison, if we substitute for the values from the illustration above, ![]() while

while ![]() Both of these values are too high for practical application. Note that the difference between the calculated potential drop and the maximum value is significant, even when we are removing 95% of the incoming metal-ion concentration. Decreasing our throughput by lowering the volumetric flow rate from 25 L·min−1 to 9 L·min−1 reduces

Both of these values are too high for practical application. Note that the difference between the calculated potential drop and the maximum value is significant, even when we are removing 95% of the incoming metal-ion concentration. Decreasing our throughput by lowering the volumetric flow rate from 25 L·min−1 to 9 L·min−1 reduces ![]() to 0.18 V, a value that may be feasible. A fraction of this decrease will be offset by a decrease in the mass-transfer coefficient with decreasing velocity, which was not considered in the calculation.

to 0.18 V, a value that may be feasible. A fraction of this decrease will be offset by a decrease in the mass-transfer coefficient with decreasing velocity, which was not considered in the calculation.

Given that there are voltage losses associated with the anodic reaction and ohmic drop across the channel separating the electrodes, that a sufficient overpotential is needed on the cathode to reach the limiting current, and that impurities may influence behavior, practical systems rarely operate at 100% current efficiency. In fact, in extreme cases current efficiencies for removal systems with low initial concentrations and high removal fractions may dip below 5%, although this is clearly not preferred. It is your job as the electrochemical engineer to understand and quantify the factors that influence electrode design and operation in order to achieve an optimal solution that meets both technical and economic constraints.

Closure

The basic concepts of a porous electrode have been introduced and the principal methods of characterizing these electrodes were discussed. The main terms used in discussing porous electrodes are shown in Figure 5.16. Additional key parameters are the porosity, specific interfacial area, pore size distribution, and surface energy. The most important feature is the increased surface area per volume. Porous electrodes are the mainstays of nearly all electrochemical systems for energy storage and conversion, such as batteries, fuel cells, electrochemical capacitors, and flow cells. Therefore, the information from this chapter is essential for the analysis of these devices in subsequent chapters. The governing equations to describe a porous electrode have been developed. Analytic solutions are possible for either linear or Tafel kinetics when concentration gradients are neglected. The distribution of current through the electrode is determined by the ratio of ohmic and kinetic resistances. Systems with a gas phase were also discussed. In particular, fuel cells require three separate phases in contact. One specific example, the flooded-agglomerate model, was used to illustrate how an effective electrode can be created.

Porous Electrode Terminology

- Front: the edge of the electrode next to the electrolyte

- Back: the edge of the electrode next to the current collector

- Porosity: the empty or void portion of the electrode

- Superficial area: the area of a plane cutting through the electrode normal to the direction of superficial current

- Specific interfacial area: the actual physical surface area of electrode in contact with the electrolyte divided by the volume of the electrode [m−1]

Further Reading

- Dullien, F.A.L. (1992) Porous Media, Fluid Transport and Pore Structure, Academic Press.

- Newman, J. and Thomas-Alyea, K.E. (2004) Electrochemical Systems, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ.

Problems

5.1. The discharge of the lead–acid battery proceeds through a dissolution/precipitation reaction. These two reactions for the negative electrode are

and

A key feature is that lead dissolves from one portion of the electrode but precipitates at another nearby spot. The solubility of Pb2+ is quite low, around 2 g·m−3. How then can high currents be achieved in the lead–acid battery?

- Assume that the dissolution and precipitation locations are separated by a distance of 1 mm with a planar geometry. Using a diffusivity of 10−9 m2·s−1 for the lead ions, estimate the maximum current that can be achieved.

- Rather than two planar electrodes, imagine a porous electrode that is also 1 mm thick made from particles with a radius 10 μm packed together with a void volume of 0.5. What is the maximum superficial current here based on the pore diameter?

- What do these results suggest about the distribution of precipitates in the electrodes?

5.2. A porous electrode is made from solid material with an intrinsic density of ρs. When particles of this material are combined to form an electrode, it has an apparent density of ρa. What is the relationship between these two densities and the porosity? Assuming the particles are spherical with a diameter of 5.0 μm, what is the specific interfacial area? If the electrode is made from particles with a density of 2100 kg·m−3 is 1 mm thick and has an apparent density of 1260 kg·m−3, by what factor has the area increased compared to the superficial area?

5.3. Calculate the pressure required to force water through a hydrophobic gas diffusion layer of PEM fuel cell. The contact angle is 140° and the average pore diameter is 20 μm. Use 0.0627 [N·m−1] for the surface tension of water.

5.4. The separator of a phosphoric acid fuel cell is comprised of micrometer and submicrometer-sized particles of SiC. Capillary forces hold the liquid acid in the interstitial spaces between particles, and this matrix provides the barrier between hydrogen and oxygen. What differential gas pressure across the matrix can be withstood? Assume an average pore size of 1 μm, and use a surface tension of 70 mN·m−1, a contact angle of 10°.

5.5. The separator used in a commercial battery is a porous polymer film with a porosity of 0.39. A series of electrical resistance measurements are made with various numbers of separators filled with electrolyte stacked together. These data are shown in the table. The thickness of each film is 25 μm, the area 2 × 10−4 m2, and the conductivity of the electrolyte is 0.78 S·m−1. Calculate the tortuosity. Why would it be beneficial to measure the resistances with increasing numbers of layers rather than just a single point?

| Number of layers | Measured resistance [Ω] |

| 1 | 1.91 |

| 2 | 3.41 |

| 3 | 5.17 |

| 4 | 6.65 |

| 5 | 7.79 |

5.6. To reach the cathode of a proton exchange-membrane fuel cell, oxygen must diffuse through a porous substrate. Normally, the porosity (volume fraction available for the gas) is 0.7 and the limiting current is 3000 A·m−2. However, liquid water is produced at the cathode with the reduction of oxygen. If this water is not removed efficiently, the pores can fill up with water, and the performance decreases dramatically. Use the Bruggeman relationship to estimate the change in limiting current when, because of the build-up of water, only 0.4 and 0.1 volume fractions are available for gas transport.

5.7. Calendering of an electrode is a finishing process used to smooth a surface and to ensure good contact between particles of active material. The electrode is passed under rollers at high pressures. If the initial thickness and porosity were 30 μm and 0.3, what is the new void fraction if the electrode is calendared to a thickness of 25 μm? What effect would this have on transport?

5.8. For a cell where σ ≫ κ, the reaction proceeds as a sharp front through the porous electrode. Material near the front of the electrode is consumed before the reaction proceeds toward the back of the electrode. This situation is shown in the figure, Ls is the thickness of the separator, Le the thickness of the electrode, and xr is the amount of reacted material.

- If the cell is discharged at a constant rate, show how the distance xr depends on time, porosity, and the capacity of the electrode, q, expressed in C·m−3.

- What is the internal resistance? Use κs and κ for the effective conductivity of the separator and electrode, respectively.

- If the cell is ohmically limited, what is the potential during the discharge?

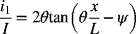

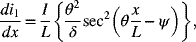

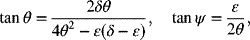

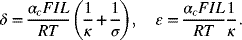

5.9. For Tafel kinetics and a one-dimensional geometry, an analytic solution is also possible analogous to the one developed for linear kinetics. The following is the solution for a cathodic process:

and

where

- Make two plots of the dimensionless current distribution (derivative of i1) for Tafel kinetics: one with Kr = 0.1 and the other with Kr = 1.0. δ is a parameter, use values of 1, 3, and 10.Hint: It may be numerically easier to first find the value of θ that corresponds to the desired value for δ.

- Compare and contrast the results in part (a) with Figures 5.6 and 5.7 for linear kinetics.

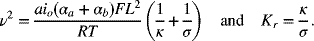

5.10. The two parameters that describe the current distribution in a porous electrode with linear kinetics in the absence of concentration gradients are

- How can the parameter ν2 be described physically?

- For the following conditions, sketch out the current distribution

across the electrode:

across the electrode:

| Kr = 1, | ν2 ≫ 1, |

| Kr = 1, | ν2 ≪ 1, |

| Kr = 0.01, | ν2 ≫ 1. |

5.11. Problem 5.9 provides the solution for the current distribution in a porous electrode with Tafel kinetics in the absence of concentration gradients. Describe the physical parameters? Compare and contrast these results with the analysis that leads to the Wa for Tafel kinetics found in Chapter 4.

5.12. The figure shows the current distribution in a porous electrode for Tafel kinetics. δ = 100 and Kr is a parameter. As expected, for such a large value of δ, the current is highly nonuniform. Further, for the values of Kr chosen, the reaction is concentrated near the back of the electrode. Here, the scale of the ordinate has been selected to emphasize the behavior at the front of the electrode. Note that in all cases, rather than getting ever smaller at the front of the electrode, the derivative of current density always goes through a minimum and is increasing at the current collector. Physically explain this behavior.

5.13. An electrode is produced with a thickness of 1 mm, κ = 10 S·m−1 and κ = 100 S·m−1. The reaction follows linear kinetics, io = 2 A·m−2 and the specific interfacial area is 104 m−1. It is proposed to use the same electrode for a second reaction where the exchange-current density is much larger, 100 A·m−2. What would be the result of using this same electrode? What changes would you propose?

5.14. The exchange-current density io does not appear in the solution for the current distribution for Tafel kinetics (see how ε is defined in Problem 5.9). Why not?

5.15. Rather than the profile shown in Figure 5.7, one might expect that for the case where σ = κ, the distribution would be uniform and not just symmetric. Show that this cannot be correct. Start by assuming that the profile is uniform; then sketch how i1 and i2 vary across the electrode. Then sketch the potentials and identify the inconsistency.

5.16. Repeat Illustration 5.3 for a more conductive electrolyte, κ = 100 S·m−1. If it is desired to keep the reaction rate at the back of the electrode no less than 40% of the front, what is the maximum thickness of the electrode? Additional kinetic data are αa = αc = 0.5, io = 100 A·m−2, a = 104 m−1. Using the thickness calculated, plot the current distribution for solutions with the following conductivities, 100, 10, 1, and 0.1 S·m−1.

5.17. Consider a similar problem to the flooded-agglomerate model developed in Section 5.6, except that now a film of electrolyte covers the agglomerate to a depth of δ. Find the expression for the rate of oxygen transport that would replace Equation 5.50.

5.18. Derive the expression for the effectiveness factor, Equation 5.53. What is the expression for a slab rather than a sphere?

5.19. A porous flow-through electrode was examined in Chapter 4 for the reduction of bromine in a Zn-Br battery.

The electrode is 0.1 m in length with a porosity of 0.55. What is the maximum superficial velocity that can be used on a 10 mM Br2 solution if the exit concentration is limited to 0.1 mM? Use the following mass-transfer correlation:

The Re is based on the diameter of the carbon particles, dp, and the superficial velocity, which make up the porous electrode.

5.20. Derive Equation 5.42. Start with Equation 5.36.

5.21. Rearrange Equation 5.57 to provide a design equation for a flow-through reactor operating at limiting current. Specifically, provide an explicit expression for L, the length of the reactor, in terms of flow rate, mass-transfer coefficient, and the desired separation.

5.22. A direct method of removing heavy metals, such as Ni2+, from a waste stream is the electrochemical deposition of the metal on a particulate bed. The goal is to achieve as low concentration of Ni at the exit for as high a flow rate as possible. A flow-through configuration is proposed. However, here only the negative electrode is porous, and the counter electrode (+) is a simple metal sheet. Would you recommend placing the counter electrode upstream or downstream of the working electrode? Why? For this analysis, assume σ ≫ κ, and that the reaction at the electrode is mass-transfer limited. Hint: Develop an expression for the change in solution potential similar to Equation 5.63.

CopycopyHighlighthighlightAdd NotenoteGet Linklink

Leave a Reply